ABOUT REMOTE HUTS

Origins Of The Website

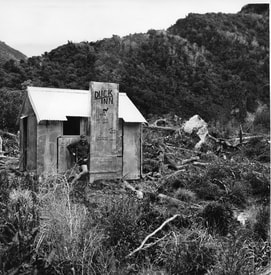

The Remote Huts website was created in 2003 to profile and raise awareness about a unique and iconic network of around 60 remote high-country huts and bivouacs in central Westland that were under threat of disappearing. After years of neglect many of the structures were becoming run-down or dilapidated. Others that were still in relatively good shape were not being visited due to unmaintained and overgrowing access routes. The Department of Conservation (DOC), responsible for administering the structures, wanted to get them off their books and had proposed removing a number of them. However, the reason they weren’t being used was because people couldn’t get to them or get hold of up-to-date route information. The generations of back-country enthusiasts that had used and enjoyed these little wilderness refuges weren’t pleased with their ongoing neglect or DOC’s proposed solution to the problem.

Permolat

The Permolat Online Group was set up in conjunction with the website and developed very rapidly into an effective volunteer collective that began carrying out maintenance on these structures and their access tracks. The Group provided a voice for a diverse range of outdoor types and was able to lobby effectively for the retention of these iconic huts and bivs. The remote hut circuits demand a higher level of skill and experience than your average great walk or tourist track but provide a wonderful alternative to the DOC managed ones that are often crowded or increasingly booked out. The online medium proved highly effective as a means of connecting and organising folk with a range of skills and experience relevant to hut maintenance and trackwork. The Permolat Group grew rapidly and was a catalyst for more widespread volunteer activity around the country. Numerous hut and track maintenance projects have been undertaken by the Group since its inception. Our original online platform became unstable as time went on and in 2021 it was shut down. The Remote Huts website was shifted to the Weebly platform and members of the online group either self-organised or shifted their activity to Permolat Facebook.

Permolat Trust

The Permolat Trust was formed and became a registered charity in 2014 in order to manage the increased complexity of funding required for the larger maintenance projects. A management agreement drawn up with DOC around the same time has allowed us to move away from individual hut maintenance contracts to a more general area-wide arrangement in central Westland.

Donations

If you use these remote facilities, or just like what we are doing and want to make a contribution, you can donate to Permolat Trust, Kiwibank, 38-9016-0266330-00. Our Charities Registration No. is CC50626, and donations are tax deductible. If you want a receipt, just email us.

Area of Operation

The Remote Huts website currently profiles 72 huts and bivs on the western side of the Southern Alps, from Karamea down to the Haast valley in South Westland. We recently added another couple from the Matakitaki catchment in Nelson Lakes NP. Most of the structures were built by the New Zealand Forest Service from the 1950's through to the 1970's, principally for animal control, but also with recreation in mind.

Our Aim

The aim of Remote Huts and Permolat was to raise and maintain awareness of the lower-use back-country facilities and encourage and support the outdoor community to take ownership of them rather than leave it to some external agent or higher authority to do it. We figure those with the greatest investment in and personal connection with these structures are best able to look after them and ensure this legacy continues for future generations. The website serves to provide the up-to-date information on hut and track conditions that will help facilitate this. We'd like to see a shift from the old entitlement mentality to one of community empowerment. This will involve user groups stepping up and taking on hut and track maintenance and developing partnerships with DOC in the areas in which the Department is unable or unwilling to undertake the role. In some places this is already happening to a large extent. Up until now we've been in the unique and privileged position of having it laid on for us, first by the New Zealand Forest Service (NZFS), and later to a lesser degree by DOC. The expectation that this would continue hasn't been grounded in reality for some time.

The Remote Huts website was created in 2003 to profile and raise awareness about a unique and iconic network of around 60 remote high-country huts and bivouacs in central Westland that were under threat of disappearing. After years of neglect many of the structures were becoming run-down or dilapidated. Others that were still in relatively good shape were not being visited due to unmaintained and overgrowing access routes. The Department of Conservation (DOC), responsible for administering the structures, wanted to get them off their books and had proposed removing a number of them. However, the reason they weren’t being used was because people couldn’t get to them or get hold of up-to-date route information. The generations of back-country enthusiasts that had used and enjoyed these little wilderness refuges weren’t pleased with their ongoing neglect or DOC’s proposed solution to the problem.

Permolat

The Permolat Online Group was set up in conjunction with the website and developed very rapidly into an effective volunteer collective that began carrying out maintenance on these structures and their access tracks. The Group provided a voice for a diverse range of outdoor types and was able to lobby effectively for the retention of these iconic huts and bivs. The remote hut circuits demand a higher level of skill and experience than your average great walk or tourist track but provide a wonderful alternative to the DOC managed ones that are often crowded or increasingly booked out. The online medium proved highly effective as a means of connecting and organising folk with a range of skills and experience relevant to hut maintenance and trackwork. The Permolat Group grew rapidly and was a catalyst for more widespread volunteer activity around the country. Numerous hut and track maintenance projects have been undertaken by the Group since its inception. Our original online platform became unstable as time went on and in 2021 it was shut down. The Remote Huts website was shifted to the Weebly platform and members of the online group either self-organised or shifted their activity to Permolat Facebook.

Permolat Trust

The Permolat Trust was formed and became a registered charity in 2014 in order to manage the increased complexity of funding required for the larger maintenance projects. A management agreement drawn up with DOC around the same time has allowed us to move away from individual hut maintenance contracts to a more general area-wide arrangement in central Westland.

Donations

If you use these remote facilities, or just like what we are doing and want to make a contribution, you can donate to Permolat Trust, Kiwibank, 38-9016-0266330-00. Our Charities Registration No. is CC50626, and donations are tax deductible. If you want a receipt, just email us.

Area of Operation

The Remote Huts website currently profiles 72 huts and bivs on the western side of the Southern Alps, from Karamea down to the Haast valley in South Westland. We recently added another couple from the Matakitaki catchment in Nelson Lakes NP. Most of the structures were built by the New Zealand Forest Service from the 1950's through to the 1970's, principally for animal control, but also with recreation in mind.

Our Aim

The aim of Remote Huts and Permolat was to raise and maintain awareness of the lower-use back-country facilities and encourage and support the outdoor community to take ownership of them rather than leave it to some external agent or higher authority to do it. We figure those with the greatest investment in and personal connection with these structures are best able to look after them and ensure this legacy continues for future generations. The website serves to provide the up-to-date information on hut and track conditions that will help facilitate this. We'd like to see a shift from the old entitlement mentality to one of community empowerment. This will involve user groups stepping up and taking on hut and track maintenance and developing partnerships with DOC in the areas in which the Department is unable or unwilling to undertake the role. In some places this is already happening to a large extent. Up until now we've been in the unique and privileged position of having it laid on for us, first by the New Zealand Forest Service (NZFS), and later to a lesser degree by DOC. The expectation that this would continue hasn't been grounded in reality for some time.

A Brief History

Around 150 huts and a connecting network of tracks and bridges were built by the NZFS, or Lands and Survey on the western side of the Southern Alps from the late 1950's to the early 1980's. Their primary function was to provide shelter for government cullers employed to curb an exploding introduced red deer population that was seriously damaging high-country ecosystems. The FS also had recreation in mind as evidenced by hut construction continuing for quite some time after the foot cullers were phased out. These structures along with huts built by alpine and tramping clubs provided New Zealand's outdoor community with a dream network of remote accommodation and trails.

In 1986 the newly created Department of Conservation took over management of high-country resources. Their spending priorities have tended to favour the more popular, high-use huts and walks, and facilities such as car parks and toilets at the tourist interface. The less frequently used huts and tracks started becoming run down or dilapidated. Footbridges that were washed away or damaged were not repaired or replaced. Overgrowing tracks deterred all but the hardiest trampers, and a lack of good quality information on routes and hut conditions compounded the situation. Decreasing levels of use justified continued low or zero maintenance, creating a spiral of disuse, and provided the bean counters with a good justification for the removal of the structures.

A key driver of the decline is DOC’s accounting system in which it pays Treasury a 7% capital asset charge a year on its huts and other structures and then gets charged depreciation, even on these 60-year-old tin shacks. The simplest maintenance such as fixing a door or roof can result in a revaluation and additional capital asset charges, so it’s no wonder DOC accountants wanted low-use huts off their books. The irony here is that Treasury’s own guidelines allow exemptions for capital asset and depreciation charges for heritage huts and tracks in national parks and on conservation land. We believe that all of the 150 structures we have an interest in preserving could easily be included and exempted.

Another exacerbating factor is an entrenched culture of safetyism and liability avoidance within the Department. Many of its internal systems are more stringent than national legal building or engineering codes. Outstanding maintenance data is fed into a convoluted planning and decision loop that often results in very little happening. This circuitous process is undertaken by a legion of planners and managers and sucks up huge amounts of resources and funding. As a result, the amount of dosh that trickles down to an operational level is significantly diminished. A hut with a roof or window leak can be left for years and suffer serious moisture damage because expenditure is denied or delayed. One of our Trust members recently notified DOC several times about broken door latch in a relatively high-use hut. After some months of inaction, he bought the parts himself and went in and fixed it.

Going back to the late 1990s, the widespread deterioration of back-country facilities was becoming patently obvious to the outdoor community, but there was action from them. Unfortunately, we'd had it so good for so long that we still thought that some higher power would eventually turn and fix things - we just needed to keep complaining. The dawning awareness that this wasn’t going to happen led to a few pragmatic and caring types going out and cutting the trails and looking after the odd hut themselves. These early adopters were not officially sanctioned and their efforts ad-hoc and unlikely to save the majority of the at-risk structures. What was needed was a more coordinated response from community groups and individuals.

The DOC 2003 High-Country Review

In 2003 DOC did an official stock-take of the 150 huts and bivs in Westland's Tai Poutini conservancy. This included a fairly tokenistic consultation with some of the user groups. The upshot of their rationalisation process was a decision to continue fully maintaining 80 of these structures. Another 60 would be minimally maintained (something that had effectively been happening for a couple of decades already) and the remainder (considered too dilapidated, unsafe, or infrequently used) were designated for removal. Loud objections and some vigorous lobbying from high-country groups resulted in a few of the huts being recategorized, however the majority were left on minimal maintenance or to be systematically removed by 2006.

Minimal Maintenance

This was defined as “minor repairs to keep a hut sanitary and watertight,” until it deteriorated past a certain point, at which time it would be removed. Ironically, the removal costs if spent on maintenance, would have been enough to give most of the huts an extra 15 to 30-year lease of life. It was pretty obvious to us that the minimal maintenance regime would lead a gradual loss by attrition of most, if not all, of the low-use huts. It was a big wake-up call and coincided quite nicely with the inception of Permolat and the Remote Huts website. Permolat struck a chord in the outdoor community’s collective psyche and became an instant hit. It’s popularity and rapid transition into a functional collective became a catalyst for folk in other areas and helped nudge DOC to be more open to having community involvement in the maintenance of its huts and tracks. In 2006 the first maintain-by-community contract was signed with me as signatory for Scottys Biv in the Taipo valley, which had initially been designated for removal. Around this time Permolat was given the official go-ahead by the Westland Conservator to work on any pre-existing tracks that weren't being maintained by DOC as long as we used traditional markers (permolat in this case - the material used by the NZFS and other agencies). The Scottys contract was followed by several others and a number of track-cutting projects in some of the remote valleys.

Around 150 huts and a connecting network of tracks and bridges were built by the NZFS, or Lands and Survey on the western side of the Southern Alps from the late 1950's to the early 1980's. Their primary function was to provide shelter for government cullers employed to curb an exploding introduced red deer population that was seriously damaging high-country ecosystems. The FS also had recreation in mind as evidenced by hut construction continuing for quite some time after the foot cullers were phased out. These structures along with huts built by alpine and tramping clubs provided New Zealand's outdoor community with a dream network of remote accommodation and trails.

In 1986 the newly created Department of Conservation took over management of high-country resources. Their spending priorities have tended to favour the more popular, high-use huts and walks, and facilities such as car parks and toilets at the tourist interface. The less frequently used huts and tracks started becoming run down or dilapidated. Footbridges that were washed away or damaged were not repaired or replaced. Overgrowing tracks deterred all but the hardiest trampers, and a lack of good quality information on routes and hut conditions compounded the situation. Decreasing levels of use justified continued low or zero maintenance, creating a spiral of disuse, and provided the bean counters with a good justification for the removal of the structures.

A key driver of the decline is DOC’s accounting system in which it pays Treasury a 7% capital asset charge a year on its huts and other structures and then gets charged depreciation, even on these 60-year-old tin shacks. The simplest maintenance such as fixing a door or roof can result in a revaluation and additional capital asset charges, so it’s no wonder DOC accountants wanted low-use huts off their books. The irony here is that Treasury’s own guidelines allow exemptions for capital asset and depreciation charges for heritage huts and tracks in national parks and on conservation land. We believe that all of the 150 structures we have an interest in preserving could easily be included and exempted.

Another exacerbating factor is an entrenched culture of safetyism and liability avoidance within the Department. Many of its internal systems are more stringent than national legal building or engineering codes. Outstanding maintenance data is fed into a convoluted planning and decision loop that often results in very little happening. This circuitous process is undertaken by a legion of planners and managers and sucks up huge amounts of resources and funding. As a result, the amount of dosh that trickles down to an operational level is significantly diminished. A hut with a roof or window leak can be left for years and suffer serious moisture damage because expenditure is denied or delayed. One of our Trust members recently notified DOC several times about broken door latch in a relatively high-use hut. After some months of inaction, he bought the parts himself and went in and fixed it.

Going back to the late 1990s, the widespread deterioration of back-country facilities was becoming patently obvious to the outdoor community, but there was action from them. Unfortunately, we'd had it so good for so long that we still thought that some higher power would eventually turn and fix things - we just needed to keep complaining. The dawning awareness that this wasn’t going to happen led to a few pragmatic and caring types going out and cutting the trails and looking after the odd hut themselves. These early adopters were not officially sanctioned and their efforts ad-hoc and unlikely to save the majority of the at-risk structures. What was needed was a more coordinated response from community groups and individuals.

The DOC 2003 High-Country Review

In 2003 DOC did an official stock-take of the 150 huts and bivs in Westland's Tai Poutini conservancy. This included a fairly tokenistic consultation with some of the user groups. The upshot of their rationalisation process was a decision to continue fully maintaining 80 of these structures. Another 60 would be minimally maintained (something that had effectively been happening for a couple of decades already) and the remainder (considered too dilapidated, unsafe, or infrequently used) were designated for removal. Loud objections and some vigorous lobbying from high-country groups resulted in a few of the huts being recategorized, however the majority were left on minimal maintenance or to be systematically removed by 2006.

Minimal Maintenance

This was defined as “minor repairs to keep a hut sanitary and watertight,” until it deteriorated past a certain point, at which time it would be removed. Ironically, the removal costs if spent on maintenance, would have been enough to give most of the huts an extra 15 to 30-year lease of life. It was pretty obvious to us that the minimal maintenance regime would lead a gradual loss by attrition of most, if not all, of the low-use huts. It was a big wake-up call and coincided quite nicely with the inception of Permolat and the Remote Huts website. Permolat struck a chord in the outdoor community’s collective psyche and became an instant hit. It’s popularity and rapid transition into a functional collective became a catalyst for folk in other areas and helped nudge DOC to be more open to having community involvement in the maintenance of its huts and tracks. In 2006 the first maintain-by-community contract was signed with me as signatory for Scottys Biv in the Taipo valley, which had initially been designated for removal. Around this time Permolat was given the official go-ahead by the Westland Conservator to work on any pre-existing tracks that weren't being maintained by DOC as long as we used traditional markers (permolat in this case - the material used by the NZFS and other agencies). The Scottys contract was followed by several others and a number of track-cutting projects in some of the remote valleys.

Crystal Biv rebuild 2019

Crystal Biv rebuild 2019

Permolat's Community Hut and Track Projects

Permolat's first group outing in 2005 was the reopening of the route up the mid Kokatahi valley from Boo Boo Hut to Crawford Junction. In 2006 the first maintain-by-community contract was signed for Scottys Biv in the Taipo valley, which had been designated for removal. Since then, the group and other volunteers have done maintenance on 35 huts and bivouacs (see the Huts page) located between the Karamea and Haast rivers. We've also managed to open up most of the old NZFS routes to these structures that DOC hadn't been maintaining, along with a number of key front country and tops access tracks. As a result, the remote back country hut and track networks on the West Coast are in better shape now than they have been for the last 50 years.

Unofficial trackwork had been occurring in certain areas prior to Permolat's inception, and from 2005 onward we began opening up some of the unmaintained and overgrown routes. An informal agreement with the Westland Conservator around 2006 allowed Permolat to work on pre-existing tracks on public conservation land that weren't being maintained by DOC. The proviso was that we used historic markers (permolat in this case) and not their orange triangles. Permolat was the name given to the venetian blind strips that were used by the NZFS to mark tracks. This trackwork is continuing and the Tracks page on this site lists their condition, maintenance status, and who is responsible for their upkeep. If you are interested in helping out have a look at it. There may be one in your area or elsewhere that needs attention. Don't be put off if there is already a name listed. That person or persons may no longer be active or be open to having help. Contact us in any case, and if you'd like to adopt a track and we can help out with contacts, resources, and gear and expense reimbursement. It is becoming increasingly common now to see loppers or pruning saws being added to the tramping kit and folk are starting to catch on that it's OK to cut an overgrown track. We'd like to see a bit of track maintenance incorporated as a matter of routine on trips on community-maintained routers and see this as a healthy paradigm shift back to a community empowerment model. Aside from the grim reality that cutting tracks is less glamourous than painting huts in beautiful alpine settings, there is a general perception that it is a complex affair involving big crews in high-viz with chainsaws and brush bars. Some ongoing education on our part may help reassure people that we’re not constructing great walks, that it’s usually a much simpler affair that quite often can done with just hand tools as an extension of normal outdoor activities, and with no added risk.

The Back Country Trust

In 2013 DOC’s CEO Lou Sanson announced there would be no more hut removals. In 2014 Conservation Nick Smith allocated $500,000 from the DOC Community Fund to establish a programme to support volunteers doing conservation and recreation work in the high country. This would formalise and scale up on what volunteer groups like Permolat were doing around the country. The funds went to a newly established Outdoor Recreation Consortium (ORC) which was an alliance of Federated Mountain Clubs (FMC), the NZ Deerstalkers Association, and TRAILS (a mountain biking organisation). The ORC began taking on a number of hut renovation projects using skilled volunteers, the success of which and high quality of work undertaken, led to its replacement in 2017 with the formation of the Back Country Trust. BCT was funded with a provisional yearly grant of 300-400k per anum to go towards volunteer hut and track projects countrywide. Its capacity was boosted during the Covid pandemic with $2million of Jobs for Nature funding. During the first decade BCT's existed it has enabled more than 900 volunteers (supported in some areas by DOC field staff, along with Jobs for Nature funded builders and workers) to clear up a significant backlog of deferred departmental maintenance. More than 280 huts and 1500km of track have received high quality maintenance, some for the first time in 30 years, at a cost of around $6m, which is a fraction of DOC’s maintenance budget over the same period. You can keep astride of the Trust's work and some of the public feedback around it on the Huts and Tracks Facebook Page.

Permolat's first group outing in 2005 was the reopening of the route up the mid Kokatahi valley from Boo Boo Hut to Crawford Junction. In 2006 the first maintain-by-community contract was signed for Scottys Biv in the Taipo valley, which had been designated for removal. Since then, the group and other volunteers have done maintenance on 35 huts and bivouacs (see the Huts page) located between the Karamea and Haast rivers. We've also managed to open up most of the old NZFS routes to these structures that DOC hadn't been maintaining, along with a number of key front country and tops access tracks. As a result, the remote back country hut and track networks on the West Coast are in better shape now than they have been for the last 50 years.

Unofficial trackwork had been occurring in certain areas prior to Permolat's inception, and from 2005 onward we began opening up some of the unmaintained and overgrown routes. An informal agreement with the Westland Conservator around 2006 allowed Permolat to work on pre-existing tracks on public conservation land that weren't being maintained by DOC. The proviso was that we used historic markers (permolat in this case) and not their orange triangles. Permolat was the name given to the venetian blind strips that were used by the NZFS to mark tracks. This trackwork is continuing and the Tracks page on this site lists their condition, maintenance status, and who is responsible for their upkeep. If you are interested in helping out have a look at it. There may be one in your area or elsewhere that needs attention. Don't be put off if there is already a name listed. That person or persons may no longer be active or be open to having help. Contact us in any case, and if you'd like to adopt a track and we can help out with contacts, resources, and gear and expense reimbursement. It is becoming increasingly common now to see loppers or pruning saws being added to the tramping kit and folk are starting to catch on that it's OK to cut an overgrown track. We'd like to see a bit of track maintenance incorporated as a matter of routine on trips on community-maintained routers and see this as a healthy paradigm shift back to a community empowerment model. Aside from the grim reality that cutting tracks is less glamourous than painting huts in beautiful alpine settings, there is a general perception that it is a complex affair involving big crews in high-viz with chainsaws and brush bars. Some ongoing education on our part may help reassure people that we’re not constructing great walks, that it’s usually a much simpler affair that quite often can done with just hand tools as an extension of normal outdoor activities, and with no added risk.

The Back Country Trust

In 2013 DOC’s CEO Lou Sanson announced there would be no more hut removals. In 2014 Conservation Nick Smith allocated $500,000 from the DOC Community Fund to establish a programme to support volunteers doing conservation and recreation work in the high country. This would formalise and scale up on what volunteer groups like Permolat were doing around the country. The funds went to a newly established Outdoor Recreation Consortium (ORC) which was an alliance of Federated Mountain Clubs (FMC), the NZ Deerstalkers Association, and TRAILS (a mountain biking organisation). The ORC began taking on a number of hut renovation projects using skilled volunteers, the success of which and high quality of work undertaken, led to its replacement in 2017 with the formation of the Back Country Trust. BCT was funded with a provisional yearly grant of 300-400k per anum to go towards volunteer hut and track projects countrywide. Its capacity was boosted during the Covid pandemic with $2million of Jobs for Nature funding. During the first decade BCT's existed it has enabled more than 900 volunteers (supported in some areas by DOC field staff, along with Jobs for Nature funded builders and workers) to clear up a significant backlog of deferred departmental maintenance. More than 280 huts and 1500km of track have received high quality maintenance, some for the first time in 30 years, at a cost of around $6m, which is a fraction of DOC’s maintenance budget over the same period. You can keep astride of the Trust's work and some of the public feedback around it on the Huts and Tracks Facebook Page.

Projects Completed In 2024

Over the past few years, a better resourced and structured BCT has taken over most of the non-DOC hut renovation and repair work. As a consequence, Permolat's focus has shifted to keeping the non-DOC maintained trails open. This work is just as important but less romantic and remains reliant on quite a small core group, mostly in the older demographic. The users of these high-country trails are not short of praise for our efforts but seem to be less enthusiastic when it comes to rolling up their sleeves and doing a bit of mahi. Over the summer of '23-'24Di Hooper and Flag McKenzie worked on route up to Mt Fleming in the northern Paparoa range, opening up the start of the track which was badly overgrowing. In Early '24 volunteers from the Peninsula Tramping Club helped with a BCT maintenance project at Griffin Creek Hut and did a bit of trackwork on the Griffin side of the Rocky Creek route. Work was started on an old NZFS route to Mt Robinson from Granite Creek near the Hokitika. Andrew Barker went back into the Johnson and did more work from Little Fugel Creek down to Johnson Hut. He also reopened some old side-routes to the old mine in Silver Creek and up onto Mt Zetland. DOC Greymouth didn't have the operational funds to do anything on the overgrowing track up the Crooked valley to Jacko Flat Hut and were happy for Permolat to picks it up. The work was started in January and completed in April by me with input from Rowan McComish and Joke de Rijke. Paulette Birchfield and friends did some work up to 600m on the Terra Quinn track in the Wanganui valley. Peter Alspach and friends did some work on the Pell Stream Hut route. In March Liam Stewart of Christchurch and his kids helped us cut and mark the Knobby Ridge route up to 800m. In April Joke de Rijke and I started tidying up the Karnbach tops route near Hari Hari (now finished), and we also redid the lower Hokitika routes as far as Frisco Hut. In May Indy Hawthorne and friends opened up an old route down into Wren Creek basin from the Allan Knob track in the Toaroha. In June Xander Wijninckx got a crew together to start cutting down from the top end of the Knobby Ridge. A generous freebie flight from Matt Newton of Precision Helicopters got us up there and started on a formidable stretch of alpine scrub. Guy McKinnon has done some work on an old tops track at Barrack Creek in the Otira and further down the valley Liz Wightwick and her CTC friends have given the track up Kellys Creek a trim. Xander Wijninckx got a crew together to cut the top end of the Knobby Ridge track on the Diedrichs Range at the end of May. I've been doing more work in the mid zones of that route. July was a very busy month. Indy Hawthorne and friends did some work clearing Browning Rang tops track from Mid Styx, reaching the 1100m contour and up to Pt, 1085m on the Pinnacle Biv track. In the same month Michal Klajban and Jan Kupka did some tidying of the Newton Range Biv routes from the Styx valley and Mt Brown Hut and Daniel Gillies and some CTC folk did some work on the Boo Boo Hut track. The Knobby Ridge and Rocky Creek Biv routes were also finished, the latter by Eigill Wahlberg.

Planned Projects

Geoff Spearpoint will continue to beaver away in the Paringa valley and at Tunnel Creek Hut, is planning to do more maintenance and trackwork at Roaring Billy Hut and on the Elcho Stream routes in the Hopkins. Glenn Johnston and John Hutt are planning some more work the route from the Styx valley to Mt Brown Hut later this winter. Tara Mulvaney is keen to do some work on the Mt Adams route in South Westland. Guy McKinnon is planning to check the upstream route onto Mt Barron in the Otira valley. Daniel Gillies will continue to work on the lower Kokatahi tracks and is interested in having a look at some of the Explorer Hut routes. Craig Benbow is planning to do a new fire surround for Waikiti Hut later in the year. We'd look at combining a bit of trackwork with that. On the BCT front plans are afoot to fix up Townsend Hut in the spring. I’ve heard that the Cone Creek Hut track is getting a bit messy, as is the Waikiti in places. Blair Skevington of the Canterbury Tramping Club is interested in doing some work on the track up the Otehake valley when it warms up more. Liz Wightwick is arranging a group to fly into Yeats Ridge Hut in September to complete some unfinished interior and exterior painting. She'll also be doing some work on the Yeats and Crystal Biv tracks. Trackwork on the Coast is never ending. Michal Klajban is planning on doing more work on the Pell Stream Hut route. All other offers of help will be gratefully accepted.

Canterbury Projects

Volunteer activity has also geared up on the Eastern side of the Alps with Permolat and Back Country Trust member Craig Benbow organising many of the projects. Other locals have chipped in as well, supported by Backcountry Trust funding. Back in the beginning some of the DOC Canterbury staff and offices were reticent about having volunteer input and in a few cases were quite obstructive. A bit of nudging from above had applied to shift this mindset. Projects have included Minchin, Murphys, Veil, Candlesticks, MacKenzie, Glenrae, Ant Stream, Mingha, Lake Man, Worsley, Lucretia, West Mathias, Canyon Creek and Nina Bivs, and Kowai, Bull Creek, Lochinvar, Cattle Creek, McCoy and Glenrae Huts. The Biv jobs have been major makeovers in most cases with other key figures being Mike Lagan and Hugh van Noorden. In April 2021 Peter Alspach took a crew into the Nina and gave Lucretia Biv replaced the fireplace, chimney and roof and relined the interior. A woodshed was also built and the toilet re-sited. Some of this work can be viewed on Canterbury Remote Basic Hut Restorations. In October 2022 Richard Janssen and others reopened the route to Stony Stream Biv in the Waiau catchment. Craig and others have been active this winter dropping in materials to start doing up Puketeraki and Turnbull bivs. In August '23 he, David Keen and Paul Reid gave Ranger Biv in the Poulter a total makeover. Frank King and Honora Renwick of Christchurch are passionate advocates for our remote back-country huts and were hut and track adopters from back before Permolat's inception. They have been busy beavering away over the years on various Canterbury tracks including Ranger Biv and Salmon Creek Biv. In early '24 they repainted the latter and also did some work on the Kellys Range route to Hunts Creek Hut in the Taipo valley. In March Geoff Spearpoint and I re-opened the old low route around Meins Knob to Lyall Hut in the Rakaia.

Non-Permolat Projects

High-country volunteer activity has achieved significant momentum around the entire country over the past few years, something we hoped would happen when we started Permolat way back. The Back Country Trust has become the main driver of projects providing access for community groups to larger amounts of funding and expertise. They received a significant boost with Covid-related Kaimahi for Nature funding that resulted in a number of projects not envisaged under the normal set-up. We had a total rebuild of Mullins Hut in the Toaroha valley in 2021 and some of our remote tracks got input including Headlong Spur in the Waitaha which was recut by Hiking NZ employees. DOC has been freed up by this and has been able to catch up on deferred maintenance on Huts like Scamper Torrent in the Waitaha valley and Top Tuke in the Mikonui catchment. In February 2021 the construction of a brand new 8-bunk hut was completed on the Mataketake Range near Haast. This was funded by a bequeath from the Andy Dennis Estate and will be owned by the BCT and co-maintained by the Trust and DOC. In 2022 the BCT re-roofed, re-piled, and re-windowed Cone Creek Hut, did some deferred maintenance on Johnson Hut in the Mokihinui and overhauled Rocky Creek Biv in the Taipo valley. In 2023 Top Olderog Biv in the Arahura was overhauled and the last of the Kamahi for Nature funding used for a rebuild of Dunns Hut in the Taipo. In 2024 the Trust carried out planned renovations of Yeats Hut in the Toaroha, Griffin Creek Hut in the Taramakau, Price Basin Hut in the Whitcombe valley, and Kiwi Hut in the Taramakau. The Yeats project was half-funded with a bequest from the late Leo Maunders of the Peninsula Tramping Club and the Griffin one with Canterbury University Tramping Club input. PTC volunteers assisted with the Griffin and Yeats projects, Permolat volunteers with Price Basin one, and community volunteers with the Kiwi Hut rebuild. DOC assisted BCT with the Kiwi hut rebuild which was funded with a generous bequest from the Henwood family in memory of their late mother who was a keen tramper.

At a more local level there are other non-permolat initiatives. Graeme Jackson of Hokitika is looking after Townsend Hut in the Taramakau and the Ross Community Group have taken over an old miner’s hut on Mt Greenland which will provide another easy front country experience for trampers. In 2022 a group of Hokitika-based rock climbers were granted consent to put a new track up onto Mt Turiwhate from the Kawaka Saddle and have completed this work.

Ruahine Group and Permolat Southland

In 2012 a Ruahine Users Group section was added to the old Permolat online platform. There had been big cutbacks in DOC's high-country maintenance programme in the Ruahine Forest park, with up to 50% of the huts being dropped from their schedule. In August 2021 they established their own Ruahine Group platform with Julia Mackie of the Napier Tramping Club as Group Administrator.

In 2017 Permolat Trust member Alastair Macdonald moved to Mataura and set up a Permolat Southland group with an associated Facebook page. The Group has charity status and there is plenty to do down that way for aspiring volunteers. Since inception the group has completed an impressive number of hut and track projects with more lined up for the coming spring/ summer period.

The situation today

Back in 2003 we would have been happy just saving a few of the at-risk huts, and never dreamed that the volunteer movement would take off in such a fashion nationwide and achieve the amazing results that it has. In our patch in Central Westland most of the huts that were at-risk or on that early remove list have been repaired or restored at a professional level and now have a good 50 or 60 more years of life in them. With BCT doing the bigger jobs Permolat has been able to step back from hut maintenance and shift its focus to keeping the remote track networks open. This is a much less romantic task and while folk are grateful for the work we do, it’s hard to get the track users themselves to take more ownership. They think Permolat is there to do it for them, which isn’t really the case. The actual group is more a concept these days than a corporeal entity. Most of the original active members have self-organised and are operating more or less autonomously. Also, our age demographic is 50+ and many of us are now retirees. The Permolat Trust continues to operate on a relatively modest budget giving out grants for smaller projects, tools, and track cutting expenses. At various times our volunteers will assist on the larger BCT projects. Earth Sea Sky gave us our first big donation of $4000 way back in our early days, and in 2013 we received a $10,000 seeding grant from DOC. Since then, the bulk of our funding has been small donations from the generous individuals who support us. We also administer the koha that come in from Mt Brown Hut users, which go back into maintaining the Hut. We recently received generous $5000 bequest from the Cotton family in Hokitika which will also go towards Mt Brown’s continued upkeep.

How You Can Help

Permolat wants to promote a culture of community ownership and responsibility for remote, low-use, high-country facilities. This includes track and hut checks and maintenance, but also keeping tabs on things and feeding back so we can update the website in real-time. If you are visiting one of the huts or using the tracks or routes covered by the website, please make a note of hut and track conditions, any changes, and use the contact link to provide updates. The high-country is constantly on the move and we want to keep the track information we provide current. If you are unsure of the maintenance status of a hut, check the relevant webpage. If you are unsure about the status of a track or want to adopt or work on one, visit the Tracks page. If there is already a name next to it, don’t be discouraged. They may no longer be actively working on it, or if they are, would be happy to have others on board. You'll also need to contact your local DOC person just to keep them in the loop. They may ask you to complete a H&S plan and we have a good downloadable template on our Links page. Permolat Trust is happy to help you work through the protocols, act as an umbrella organisation if this is required, and will consider reimbursing you for gear bought specifically for trackwork and other related expenses. We’d really like to see a greater level of track adoption and once you have an emotional investment in a trail it's very hard to let it run down. Going back in once a year is a small investment but the regular attention need only be minimal to keep things in good order. If a hut or track is DOC maintained, they still need to be informed about any issues or repairs needed from their end of things.

We encourage all outdoor types to make some lightweight loppers and a small fold-up pruning saw as part of your kit when using tracks that aren't officially maintained. An amazing amount can be done with these simple tools to keep the trails open. A roll of cruise tape is handy for keeping key entry and exit points marked, and for marking routes around windthrow. Build rock cairns at these places if existing markers have been obscured or washed out.

DOC Involvement and Recent Changes

DOC field staff on the Coast have always been supportive of Permolat and regularly assist us and other community groups with projects. They have often provided materials, hut paint and have done backloads to hut sites when doing their own work in the area. We co-work on some of their projects and volunteers can sometimes accompany DOC maintenance staff on official projects. Permolat Trust has a general management agreement with them that allows us to work on multiple huts and tracks across the province. DOC's Director General from 2013 to 2021 Lou Sanson, grew up in Hokitika and used the local networks extensively when he was younger. Having him as an ally at the top of the Department over that period was incredibly fortuitous for the volunteer movement. His 2IC Mike Slater (since retired) was instrumental in nudging some of the more obstructive conservancies or individuals in the hierarchy to behave more cooperatively with community groups. It will be interesting to see what happens now under the new leadership.

Over the past few years, a better resourced and structured BCT has taken over most of the non-DOC hut renovation and repair work. As a consequence, Permolat's focus has shifted to keeping the non-DOC maintained trails open. This work is just as important but less romantic and remains reliant on quite a small core group, mostly in the older demographic. The users of these high-country trails are not short of praise for our efforts but seem to be less enthusiastic when it comes to rolling up their sleeves and doing a bit of mahi. Over the summer of '23-'24Di Hooper and Flag McKenzie worked on route up to Mt Fleming in the northern Paparoa range, opening up the start of the track which was badly overgrowing. In Early '24 volunteers from the Peninsula Tramping Club helped with a BCT maintenance project at Griffin Creek Hut and did a bit of trackwork on the Griffin side of the Rocky Creek route. Work was started on an old NZFS route to Mt Robinson from Granite Creek near the Hokitika. Andrew Barker went back into the Johnson and did more work from Little Fugel Creek down to Johnson Hut. He also reopened some old side-routes to the old mine in Silver Creek and up onto Mt Zetland. DOC Greymouth didn't have the operational funds to do anything on the overgrowing track up the Crooked valley to Jacko Flat Hut and were happy for Permolat to picks it up. The work was started in January and completed in April by me with input from Rowan McComish and Joke de Rijke. Paulette Birchfield and friends did some work up to 600m on the Terra Quinn track in the Wanganui valley. Peter Alspach and friends did some work on the Pell Stream Hut route. In March Liam Stewart of Christchurch and his kids helped us cut and mark the Knobby Ridge route up to 800m. In April Joke de Rijke and I started tidying up the Karnbach tops route near Hari Hari (now finished), and we also redid the lower Hokitika routes as far as Frisco Hut. In May Indy Hawthorne and friends opened up an old route down into Wren Creek basin from the Allan Knob track in the Toaroha. In June Xander Wijninckx got a crew together to start cutting down from the top end of the Knobby Ridge. A generous freebie flight from Matt Newton of Precision Helicopters got us up there and started on a formidable stretch of alpine scrub. Guy McKinnon has done some work on an old tops track at Barrack Creek in the Otira and further down the valley Liz Wightwick and her CTC friends have given the track up Kellys Creek a trim. Xander Wijninckx got a crew together to cut the top end of the Knobby Ridge track on the Diedrichs Range at the end of May. I've been doing more work in the mid zones of that route. July was a very busy month. Indy Hawthorne and friends did some work clearing Browning Rang tops track from Mid Styx, reaching the 1100m contour and up to Pt, 1085m on the Pinnacle Biv track. In the same month Michal Klajban and Jan Kupka did some tidying of the Newton Range Biv routes from the Styx valley and Mt Brown Hut and Daniel Gillies and some CTC folk did some work on the Boo Boo Hut track. The Knobby Ridge and Rocky Creek Biv routes were also finished, the latter by Eigill Wahlberg.

Planned Projects

Geoff Spearpoint will continue to beaver away in the Paringa valley and at Tunnel Creek Hut, is planning to do more maintenance and trackwork at Roaring Billy Hut and on the Elcho Stream routes in the Hopkins. Glenn Johnston and John Hutt are planning some more work the route from the Styx valley to Mt Brown Hut later this winter. Tara Mulvaney is keen to do some work on the Mt Adams route in South Westland. Guy McKinnon is planning to check the upstream route onto Mt Barron in the Otira valley. Daniel Gillies will continue to work on the lower Kokatahi tracks and is interested in having a look at some of the Explorer Hut routes. Craig Benbow is planning to do a new fire surround for Waikiti Hut later in the year. We'd look at combining a bit of trackwork with that. On the BCT front plans are afoot to fix up Townsend Hut in the spring. I’ve heard that the Cone Creek Hut track is getting a bit messy, as is the Waikiti in places. Blair Skevington of the Canterbury Tramping Club is interested in doing some work on the track up the Otehake valley when it warms up more. Liz Wightwick is arranging a group to fly into Yeats Ridge Hut in September to complete some unfinished interior and exterior painting. She'll also be doing some work on the Yeats and Crystal Biv tracks. Trackwork on the Coast is never ending. Michal Klajban is planning on doing more work on the Pell Stream Hut route. All other offers of help will be gratefully accepted.

Canterbury Projects

Volunteer activity has also geared up on the Eastern side of the Alps with Permolat and Back Country Trust member Craig Benbow organising many of the projects. Other locals have chipped in as well, supported by Backcountry Trust funding. Back in the beginning some of the DOC Canterbury staff and offices were reticent about having volunteer input and in a few cases were quite obstructive. A bit of nudging from above had applied to shift this mindset. Projects have included Minchin, Murphys, Veil, Candlesticks, MacKenzie, Glenrae, Ant Stream, Mingha, Lake Man, Worsley, Lucretia, West Mathias, Canyon Creek and Nina Bivs, and Kowai, Bull Creek, Lochinvar, Cattle Creek, McCoy and Glenrae Huts. The Biv jobs have been major makeovers in most cases with other key figures being Mike Lagan and Hugh van Noorden. In April 2021 Peter Alspach took a crew into the Nina and gave Lucretia Biv replaced the fireplace, chimney and roof and relined the interior. A woodshed was also built and the toilet re-sited. Some of this work can be viewed on Canterbury Remote Basic Hut Restorations. In October 2022 Richard Janssen and others reopened the route to Stony Stream Biv in the Waiau catchment. Craig and others have been active this winter dropping in materials to start doing up Puketeraki and Turnbull bivs. In August '23 he, David Keen and Paul Reid gave Ranger Biv in the Poulter a total makeover. Frank King and Honora Renwick of Christchurch are passionate advocates for our remote back-country huts and were hut and track adopters from back before Permolat's inception. They have been busy beavering away over the years on various Canterbury tracks including Ranger Biv and Salmon Creek Biv. In early '24 they repainted the latter and also did some work on the Kellys Range route to Hunts Creek Hut in the Taipo valley. In March Geoff Spearpoint and I re-opened the old low route around Meins Knob to Lyall Hut in the Rakaia.

Non-Permolat Projects

High-country volunteer activity has achieved significant momentum around the entire country over the past few years, something we hoped would happen when we started Permolat way back. The Back Country Trust has become the main driver of projects providing access for community groups to larger amounts of funding and expertise. They received a significant boost with Covid-related Kaimahi for Nature funding that resulted in a number of projects not envisaged under the normal set-up. We had a total rebuild of Mullins Hut in the Toaroha valley in 2021 and some of our remote tracks got input including Headlong Spur in the Waitaha which was recut by Hiking NZ employees. DOC has been freed up by this and has been able to catch up on deferred maintenance on Huts like Scamper Torrent in the Waitaha valley and Top Tuke in the Mikonui catchment. In February 2021 the construction of a brand new 8-bunk hut was completed on the Mataketake Range near Haast. This was funded by a bequeath from the Andy Dennis Estate and will be owned by the BCT and co-maintained by the Trust and DOC. In 2022 the BCT re-roofed, re-piled, and re-windowed Cone Creek Hut, did some deferred maintenance on Johnson Hut in the Mokihinui and overhauled Rocky Creek Biv in the Taipo valley. In 2023 Top Olderog Biv in the Arahura was overhauled and the last of the Kamahi for Nature funding used for a rebuild of Dunns Hut in the Taipo. In 2024 the Trust carried out planned renovations of Yeats Hut in the Toaroha, Griffin Creek Hut in the Taramakau, Price Basin Hut in the Whitcombe valley, and Kiwi Hut in the Taramakau. The Yeats project was half-funded with a bequest from the late Leo Maunders of the Peninsula Tramping Club and the Griffin one with Canterbury University Tramping Club input. PTC volunteers assisted with the Griffin and Yeats projects, Permolat volunteers with Price Basin one, and community volunteers with the Kiwi Hut rebuild. DOC assisted BCT with the Kiwi hut rebuild which was funded with a generous bequest from the Henwood family in memory of their late mother who was a keen tramper.

At a more local level there are other non-permolat initiatives. Graeme Jackson of Hokitika is looking after Townsend Hut in the Taramakau and the Ross Community Group have taken over an old miner’s hut on Mt Greenland which will provide another easy front country experience for trampers. In 2022 a group of Hokitika-based rock climbers were granted consent to put a new track up onto Mt Turiwhate from the Kawaka Saddle and have completed this work.

Ruahine Group and Permolat Southland

In 2012 a Ruahine Users Group section was added to the old Permolat online platform. There had been big cutbacks in DOC's high-country maintenance programme in the Ruahine Forest park, with up to 50% of the huts being dropped from their schedule. In August 2021 they established their own Ruahine Group platform with Julia Mackie of the Napier Tramping Club as Group Administrator.

In 2017 Permolat Trust member Alastair Macdonald moved to Mataura and set up a Permolat Southland group with an associated Facebook page. The Group has charity status and there is plenty to do down that way for aspiring volunteers. Since inception the group has completed an impressive number of hut and track projects with more lined up for the coming spring/ summer period.

The situation today

Back in 2003 we would have been happy just saving a few of the at-risk huts, and never dreamed that the volunteer movement would take off in such a fashion nationwide and achieve the amazing results that it has. In our patch in Central Westland most of the huts that were at-risk or on that early remove list have been repaired or restored at a professional level and now have a good 50 or 60 more years of life in them. With BCT doing the bigger jobs Permolat has been able to step back from hut maintenance and shift its focus to keeping the remote track networks open. This is a much less romantic task and while folk are grateful for the work we do, it’s hard to get the track users themselves to take more ownership. They think Permolat is there to do it for them, which isn’t really the case. The actual group is more a concept these days than a corporeal entity. Most of the original active members have self-organised and are operating more or less autonomously. Also, our age demographic is 50+ and many of us are now retirees. The Permolat Trust continues to operate on a relatively modest budget giving out grants for smaller projects, tools, and track cutting expenses. At various times our volunteers will assist on the larger BCT projects. Earth Sea Sky gave us our first big donation of $4000 way back in our early days, and in 2013 we received a $10,000 seeding grant from DOC. Since then, the bulk of our funding has been small donations from the generous individuals who support us. We also administer the koha that come in from Mt Brown Hut users, which go back into maintaining the Hut. We recently received generous $5000 bequest from the Cotton family in Hokitika which will also go towards Mt Brown’s continued upkeep.

How You Can Help

Permolat wants to promote a culture of community ownership and responsibility for remote, low-use, high-country facilities. This includes track and hut checks and maintenance, but also keeping tabs on things and feeding back so we can update the website in real-time. If you are visiting one of the huts or using the tracks or routes covered by the website, please make a note of hut and track conditions, any changes, and use the contact link to provide updates. The high-country is constantly on the move and we want to keep the track information we provide current. If you are unsure of the maintenance status of a hut, check the relevant webpage. If you are unsure about the status of a track or want to adopt or work on one, visit the Tracks page. If there is already a name next to it, don’t be discouraged. They may no longer be actively working on it, or if they are, would be happy to have others on board. You'll also need to contact your local DOC person just to keep them in the loop. They may ask you to complete a H&S plan and we have a good downloadable template on our Links page. Permolat Trust is happy to help you work through the protocols, act as an umbrella organisation if this is required, and will consider reimbursing you for gear bought specifically for trackwork and other related expenses. We’d really like to see a greater level of track adoption and once you have an emotional investment in a trail it's very hard to let it run down. Going back in once a year is a small investment but the regular attention need only be minimal to keep things in good order. If a hut or track is DOC maintained, they still need to be informed about any issues or repairs needed from their end of things.

We encourage all outdoor types to make some lightweight loppers and a small fold-up pruning saw as part of your kit when using tracks that aren't officially maintained. An amazing amount can be done with these simple tools to keep the trails open. A roll of cruise tape is handy for keeping key entry and exit points marked, and for marking routes around windthrow. Build rock cairns at these places if existing markers have been obscured or washed out.

DOC Involvement and Recent Changes

DOC field staff on the Coast have always been supportive of Permolat and regularly assist us and other community groups with projects. They have often provided materials, hut paint and have done backloads to hut sites when doing their own work in the area. We co-work on some of their projects and volunteers can sometimes accompany DOC maintenance staff on official projects. Permolat Trust has a general management agreement with them that allows us to work on multiple huts and tracks across the province. DOC's Director General from 2013 to 2021 Lou Sanson, grew up in Hokitika and used the local networks extensively when he was younger. Having him as an ally at the top of the Department over that period was incredibly fortuitous for the volunteer movement. His 2IC Mike Slater (since retired) was instrumental in nudging some of the more obstructive conservancies or individuals in the hierarchy to behave more cooperatively with community groups. It will be interesting to see what happens now under the new leadership.

Remaining Barriers

A consequence of the Cave Creek tragedy back in the 1900s was the development of a pervasive culture of safteyism and extreme risk aversion within DOC. This sometimes results in attempts to micromanage (bureaucratic overreach) perfectly competent volunteers. This is not unique to DOC and is a characteristic of many of our bureaucracies. We have a burgeoning and bloated compliance industry that thrives in these higher echelons and whose main raison d'étre appears to be that of stifling productivity, creativity, and innovation. Many of the regulations have been developed for urban building sites and aren't relevant or necessary for basic huts. A mind-boggling example is that of our two metre long, bivouacs needing to have a fire exit sign on their one and only door. DOC have spent hundreds of thousands of dollars flying in workers to install guard rails on the top bunks of their huts without any clear evidence that people are dying or injuring themselves en masse by falling out of them. Things like this (and there are many more) severely reduce funds available for operating budgets, and basics like weatherproofing or maintenance of huts and bridges. The volunteers involved in the back-country movement have a collective wealth of skills and experience in risk management for which a very hands-off approach by the Department would be more than adequate.

H&S risk matrices these days are predicated on something called "base rate neglect." This is where you prioritise what is casually possible, rather than statistically probable so that something with a low probability of happening, but potential high lethality, is considered high-risk. Driving your car to the supermarket would be high-risk using this criterion, possibly even getting out of bed in the morning. A dead rat in a water tank at a hut in Nelson Lakes leads to boil water signs being flown in and installed in every hut in the country, most of which have better water quality than your average town water supply. Managing risk is an integral part of the challenge and mystique of any remote wilderness experience and so a lot of top-down compliance regimes end up being disempowering and as frustrating for DOC staff as they are for volunteers. People think that DOC is grossly underfunded and should be given more money, but the more that goes into an ineffectual system, the less effective it becomes. One of Lou Sanson’s goals was to reduce staff numbers at head office, something he failed to do. Since 2017 DOC has employed 800 more staff, while less work is being done in the field. Compare this with the outstanding efficiencies achieved by the BCT over that time and you can see how some in the hierarchy might feel threatened by what is happening at the community interface.

A Two-Tier Back-Country System

A two-tier system of high-country facilities has been developing over the past couple of decades. The first is often crowded, expensive, super-safe and sanitised, and utilised mostly by overseas travellers. Palatial huts are constructed costing millions of dollars, streams are bridged, bluffs fenced off, elaborate and unnecessary structures abound surrounded by clusters of warning signs. The second system still exists pretty much off the radar and comprises the not too insignificant remnants of the old NZFS networks. This is a zone of simple shelters and rough unformed tracks and is the preferred abode of the remote hutter, along with increasing numbers of others wanting to escape high hut fees and the tourist hoards. In this parallel universe there is great beauty, simplicity, and the opportunity to experience true wilderness solitude. A zone in which self-responsibility, self-sufficiency, risk and challenge, are essential ingredients of the journey. The volunteers that are active in this realm are reputedly four times more cost effective than DOC is. Not being paid wages doesn't appear to be a major factor. into these efficiencies. Maybe it's a love of the outdoors, the organic, non-hierarchical, networks, the huge skill and experience base, and the freedom to innovate and be creative that is the magic formula.

A consequence of the Cave Creek tragedy back in the 1900s was the development of a pervasive culture of safteyism and extreme risk aversion within DOC. This sometimes results in attempts to micromanage (bureaucratic overreach) perfectly competent volunteers. This is not unique to DOC and is a characteristic of many of our bureaucracies. We have a burgeoning and bloated compliance industry that thrives in these higher echelons and whose main raison d'étre appears to be that of stifling productivity, creativity, and innovation. Many of the regulations have been developed for urban building sites and aren't relevant or necessary for basic huts. A mind-boggling example is that of our two metre long, bivouacs needing to have a fire exit sign on their one and only door. DOC have spent hundreds of thousands of dollars flying in workers to install guard rails on the top bunks of their huts without any clear evidence that people are dying or injuring themselves en masse by falling out of them. Things like this (and there are many more) severely reduce funds available for operating budgets, and basics like weatherproofing or maintenance of huts and bridges. The volunteers involved in the back-country movement have a collective wealth of skills and experience in risk management for which a very hands-off approach by the Department would be more than adequate.

H&S risk matrices these days are predicated on something called "base rate neglect." This is where you prioritise what is casually possible, rather than statistically probable so that something with a low probability of happening, but potential high lethality, is considered high-risk. Driving your car to the supermarket would be high-risk using this criterion, possibly even getting out of bed in the morning. A dead rat in a water tank at a hut in Nelson Lakes leads to boil water signs being flown in and installed in every hut in the country, most of which have better water quality than your average town water supply. Managing risk is an integral part of the challenge and mystique of any remote wilderness experience and so a lot of top-down compliance regimes end up being disempowering and as frustrating for DOC staff as they are for volunteers. People think that DOC is grossly underfunded and should be given more money, but the more that goes into an ineffectual system, the less effective it becomes. One of Lou Sanson’s goals was to reduce staff numbers at head office, something he failed to do. Since 2017 DOC has employed 800 more staff, while less work is being done in the field. Compare this with the outstanding efficiencies achieved by the BCT over that time and you can see how some in the hierarchy might feel threatened by what is happening at the community interface.

A Two-Tier Back-Country System

A two-tier system of high-country facilities has been developing over the past couple of decades. The first is often crowded, expensive, super-safe and sanitised, and utilised mostly by overseas travellers. Palatial huts are constructed costing millions of dollars, streams are bridged, bluffs fenced off, elaborate and unnecessary structures abound surrounded by clusters of warning signs. The second system still exists pretty much off the radar and comprises the not too insignificant remnants of the old NZFS networks. This is a zone of simple shelters and rough unformed tracks and is the preferred abode of the remote hutter, along with increasing numbers of others wanting to escape high hut fees and the tourist hoards. In this parallel universe there is great beauty, simplicity, and the opportunity to experience true wilderness solitude. A zone in which self-responsibility, self-sufficiency, risk and challenge, are essential ingredients of the journey. The volunteers that are active in this realm are reputedly four times more cost effective than DOC is. Not being paid wages doesn't appear to be a major factor. into these efficiencies. Maybe it's a love of the outdoors, the organic, non-hierarchical, networks, the huge skill and experience base, and the freedom to innovate and be creative that is the magic formula.

A Short Summary

Our need for connection with nature is primordial, enigmatic, and powerful. It propels us out of air-conditioned offices and cosy cafes into remote valleys where crude shelters beckon, with curls of smoke rising from their chimneys, and views to take the breath away. The imprint of these places once experienced, draws us back irresistibly time and again. Pressure continues to mount on the higher-use facilities. The management of the tourism/ recreation interface, often serves political and corporate agendas, has been poor or piecemeal, and led to overcrowding or rationing of the more popular circuits. The wilderness is commodified in outdoor magazines, experiences are bought and accumulated like material possessions and destinations are determined by search engine algorithms. The revitalisation of the old remote hut and track system is in many ways an inevitable consequence of all of this. A regression maybe, or perhaps just a yearning for something simpler and more essential. Who better to look after this magical realm than those who care about it the most.

Our need for connection with nature is primordial, enigmatic, and powerful. It propels us out of air-conditioned offices and cosy cafes into remote valleys where crude shelters beckon, with curls of smoke rising from their chimneys, and views to take the breath away. The imprint of these places once experienced, draws us back irresistibly time and again. Pressure continues to mount on the higher-use facilities. The management of the tourism/ recreation interface, often serves political and corporate agendas, has been poor or piecemeal, and led to overcrowding or rationing of the more popular circuits. The wilderness is commodified in outdoor magazines, experiences are bought and accumulated like material possessions and destinations are determined by search engine algorithms. The revitalisation of the old remote hut and track system is in many ways an inevitable consequence of all of this. A regression maybe, or perhaps just a yearning for something simpler and more essential. Who better to look after this magical realm than those who care about it the most.

The Ubiquitous Disclaimer

EXPERIENCE, PHYSICAL FITNESS, AND ADEQUATE GEAR AND PROVISIONS ARE ESSENTIAL FOR VENTURING INTO THE REMOTE HUT ZONE!!! This means experience in the New Zealand high-country, not Alaska, or the Swiss Alps. Experience in other parts of the world will still be lacking some of the unique skill sets essential for an enjoyable and safe experience over here. There is bush and river travel, unformed or overgrown tracks, untracked alpine routes, and weather!! Many of the huts and bivs on this site are in remote rugged, settings and some can only be accessed by high-altitude routes. Being equipped for winter in midsummer may seem strange to an outsider but our high-country weather is extreme and can change from sun to blizzard in in a matter of hours at any time of the year. The 10km wide strip on the West Coast's frontal ranges gets around 10 metres of rain each year and most of the huts on this website are situated in this band. The Cropp River in the Whitcombe valley holds the NZ record of 1049mm rain over a 48-hour period in 1995. It is the third wettest place in the world. Rivers and side-creeks rise rapidly during heavy rain and become impossible to ford and most are unbridged. Following untracked rivers or creeks needs to be done with prior knowledge of their navigability due to the numerous waterfalls and gorges that typify watercourses here. Alpine crossings above 1500m are likely to be snow covered from winter through to early summer. The snow tends to burn off below 1800m in most places by late summer and the high tops may remain bare into early winter. Heavy snowfalls are more common in winter, but can occur at any time of the year. Ice axes, crampons, and ropes will be needed for some crossings during the colder months. The bushline and permanent snowline are much lower here than they are in Europe or parts of North America, If you are not experienced in all or any of the above, get yourself a guide who is, or talk to DOC or us about an easier walk.

Track And Travel Times On This Website

We frequently get feedback that the travel times posted on the website are unrealistic or even impossible, however they are based on what could reasonably be expected from someone who is fit and experienced in this type of terrain. They should not be compared with the times provided for tourist grade tracks or great walks other parts of the country which have been calibrated to take into account the less experienced and fit. Track times can also vary considerably with weather conditions, and may alter overnight due to slips, washouts and tree fall. Estimates for tops travel are for the snow-free months, late summer and autumn. Travel can be just as fast in winter if the snow is firm, or considerably slower if the snow is soft or icy.

Contact Us

Information, updates, comments, suggestions and offers of help can be emailed from our contact page. There is also Permolat Facebook which allows you to connect with others who share an interest in hut and track preservation and maintenance activities.

Thanks

A warm thanks to all who have supported us over the years with their time, labour, photos, support, feedback, donations and encouragement. From the Permolat Trustees: Craig Benbow, Andrew Buglass, Joke de Rijke, Alan Jemison, Paul Reid, Geoff Spearpoint and Hugh van Noorden.

EXPERIENCE, PHYSICAL FITNESS, AND ADEQUATE GEAR AND PROVISIONS ARE ESSENTIAL FOR VENTURING INTO THE REMOTE HUT ZONE!!! This means experience in the New Zealand high-country, not Alaska, or the Swiss Alps. Experience in other parts of the world will still be lacking some of the unique skill sets essential for an enjoyable and safe experience over here. There is bush and river travel, unformed or overgrown tracks, untracked alpine routes, and weather!! Many of the huts and bivs on this site are in remote rugged, settings and some can only be accessed by high-altitude routes. Being equipped for winter in midsummer may seem strange to an outsider but our high-country weather is extreme and can change from sun to blizzard in in a matter of hours at any time of the year. The 10km wide strip on the West Coast's frontal ranges gets around 10 metres of rain each year and most of the huts on this website are situated in this band. The Cropp River in the Whitcombe valley holds the NZ record of 1049mm rain over a 48-hour period in 1995. It is the third wettest place in the world. Rivers and side-creeks rise rapidly during heavy rain and become impossible to ford and most are unbridged. Following untracked rivers or creeks needs to be done with prior knowledge of their navigability due to the numerous waterfalls and gorges that typify watercourses here. Alpine crossings above 1500m are likely to be snow covered from winter through to early summer. The snow tends to burn off below 1800m in most places by late summer and the high tops may remain bare into early winter. Heavy snowfalls are more common in winter, but can occur at any time of the year. Ice axes, crampons, and ropes will be needed for some crossings during the colder months. The bushline and permanent snowline are much lower here than they are in Europe or parts of North America, If you are not experienced in all or any of the above, get yourself a guide who is, or talk to DOC or us about an easier walk.

Track And Travel Times On This Website

We frequently get feedback that the travel times posted on the website are unrealistic or even impossible, however they are based on what could reasonably be expected from someone who is fit and experienced in this type of terrain. They should not be compared with the times provided for tourist grade tracks or great walks other parts of the country which have been calibrated to take into account the less experienced and fit. Track times can also vary considerably with weather conditions, and may alter overnight due to slips, washouts and tree fall. Estimates for tops travel are for the snow-free months, late summer and autumn. Travel can be just as fast in winter if the snow is firm, or considerably slower if the snow is soft or icy.

Contact Us

Information, updates, comments, suggestions and offers of help can be emailed from our contact page. There is also Permolat Facebook which allows you to connect with others who share an interest in hut and track preservation and maintenance activities.

Thanks

A warm thanks to all who have supported us over the years with their time, labour, photos, support, feedback, donations and encouragement. From the Permolat Trustees: Craig Benbow, Andrew Buglass, Joke de Rijke, Alan Jemison, Paul Reid, Geoff Spearpoint and Hugh van Noorden.